The monk fruit offers the product developer a relatively new natural high intensity sweetener. Monk fruit is a small, sweet melon found mainly in China but also South-East Asia and has been used both as herbal medicine and sweetener for hundreds of years. It has recently become a serious rival to stevia in food product development.

The fruit’s traditional Chinese name is luo han guo, and often goes by this name. In some areas it is known as lo han kuo, angel fruit, arhat fruit and rakanka (Japan).

Historical Background To The Use Of Lo Han Guo (Monk Fruit) Fruit

The extract comes from the fruit, Siraitia grosvenori (Swingle). The plant itself is a perennial vine in the cucumber and melon family (Curcurbiatceae). The plant has been cultivated for centuries in China. The dried fruits are used whole, powdered or in block forms to make seasonings, beverages and traditional medicines. The first recorded writings about monk fruit come from China in around 800 AD. The fruit was sold in the US in the late 1800s and has grown in value for its opportunities in flavouring products.

Cultivation Of The Vine

The vine needs humid, almost jungle conditions to grow. It will not survive frost or extreme heat and requires 7 to 8 hours of sunlight every day to produce fruit. In mass cultivation, the flowers are hand-pollinated as used to be the practice with cucumber and certain types of squash.

The vine is usually grown on hillsides. About 90 per cent of the global supply is grown in Guangxi province of southern China. It is grown on overhead trellis planking, netting or wires hung between posts which can be seen in the picture.

Processing Monk Fruit

Production of extracts was traditionally conducted by drying the fruit over fire which gave it an added smoky note. By 1995, a method for producing clean-tasting extracts from the fruit was devised and is now the modern production method for producing both fruit concentrates or powdered extracts.

The process begins by mechanically crushing or shredding the fruit followed by extraction for 30 to 40 minutes at 80 °Cent. with deionised water. The supernatant is cooled to 50 °Cent. then clarified by passing the liquid through ultrafiltration membranes to remove pectin and large proteins. The permeate from membrane processing is mixed with an ion-exchange or adsorption resin to bind organic molecules including the mogrosides. Unwanted molecules such as sugars and mineral salts either do not bind or are eluted off the resin. Aqueous ethanol is the preferred elution solvent.

The eluent or extracted liquor is partially concentrated under reduced pressure and then decolourised sometimes using activated charcoal. Further concentration of the eluent liquor to 40 per cent soluble solids is necessary to produce a commercial liquid extract or it is spray dried at 120 °Cent. to produce a powder.

Uses Of The Monk Fruit Sweetener

Luo Han Guo, monk fruit or rakanka extract has a sweetness which is about 300 times sweeter than the equivalent amount of sugar. However, it has a slight liqourice and lingering aftertaste. It also has slight traces of bitterness at higher concentrations.

It has good heat stability which makes it suited to beverage processing. Proctor & Gamble patented the extract in 1995 for its ability to suppress off-tastes in other foods and sweeteners such as stevia. It is often used in combination with other sweetener types for this purpose.

Monk fruit offers a pronounced delayed sweetness compared to rebaudioside A with a predominantly lingering sweetness. The extract is thought to lose some of its sweetness when in an acidic solution at around pH3 compared to a neutral pH. Given that most beverages are in the pH 2.8 to 3.5 range, development work is needed to establish an appropriate balance in sweetness with other fruit components and acids. Careful thought needs to be given too to development of products where sweetness is not required early in the sensory response. We discuss this aspect later in some of the applications known about.

The extract is marketed as having either low or zero calories. Being fruit derived might make it more attractive than stevia which is plant-based. Sales of products using monk fruit shot up rapidly after the FDA classified the sweetener as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) in 2010. In 2011, the retail market research group SPINS noted the range of products using monk fruit extract increased by 42% where it was applied to natural and speciality or gourmet offerings. It is appearing increasingly in herbal and tabletop products and commands a larger share of the mainstream market. In 2012-2013, it took sales of about $60 million having seen a further 70% growth compared to last year.

Componentry

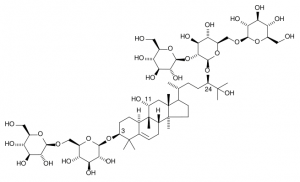

The componentry of monk fruit is made up of 5 different sweet mogrosides which are complex triterpene glycosides otherwise known as curcurbitan glycosides.

The mogrosides comprise 1 per cent or more of the dried fruit of which 50 per cent of this is mogroside V. Commercial extracts range from 30 to 90 per cent total mogrosides (II, III, IV, V and VI). The mogrosides IV, V and VI are the sweetest. The mogroside V content determines the overall sweetness of any commercial extract. There is a push from manufacturers to develop extracts with increasing levels of mogroside V. Levels of 50 percent or more are increasingly common.

A pure mogroside V powder or extract is available.

The non-mogroside material in extracts is mainly protein, carbohydrates including flavonoids and melanoidins.

Use Of Monk Fruit (Luo Han Guo Fruit) Extracts In Products

The dried extracts have a light beige colour and can be milled to a fine powder with a mild, fruity odour. The mogrosides in the extract are soluble in water. The extract also shows high stability to heat processing but little data exists on the ‘cook value’ for the main components.

Some suppliers claim the mogrosides are stable to UHT and retort processing. There is pH stability between 3 and 7. The reason for the robustness of the extract is said to be due to coordinate covalent bonds between the triterpene molceule framework and carbohydrate residues which are attached at Carbons 3 and 24 on the molecule. The mogrosides are also stable to enzymic degradation.

Where monk fruit extract has been used as the sole sweetener ingredient in food systems, there is good agreement that it is best used where a quick sweetness response is not required. It may be the case that products which rely for impact on texture or initial flavour are best. Chocolate milk, coffee are good examples. In chocolate milk, the dairy flavour and texture helps mask the lack of sweetness in the initial phase. The residual or long-lasting flavour in coffee helps to mask or minimise the sweetness that lingers with monk fruit extract.

A blend of monk fruit extract with rebaudioside A in a 1:1 weight basis ratio is claimed to be effective in many beverage applications. It relies on the quick onset of sweetness from rebaudioside A before the mogroside ‘kicks in’. The sweetness of the mogroside covers the unpleasant bitterness in the aftertaste of the rebaudioside A.

Monk fruit extract works well with calorific sweeteners and is used in reduced calorie beverages where the amount of sugar for example can be reduced by 50 per cent.

Non-beverage applications include granola, bars, cereals, baked goods, yogurt, ice cream. In Japan, rakanka extract as it is known is used in over-the-counter medicines and pharmaceutical medicines.

Metabolism Of Mogrosides.

Mogrosides are not known to be metabolised and have been given a zero calorie value. According to various citations and publication in the GRAS system, the extract does not affect blood glucose levels which implies it has no diabetic influence i.e. is non-insulinogenic. None of the mogrosides are fermented by colonic bacteria, flora or fauna.

The GRAS status was given because luo han guo (monk fruit) extracts have been used for many years and no toxicity effects have been observed in animal studies.

There is a small amount of evidence that the extracts might reduce the impact of diabetes in a mouse model but this has not been substantially confirmed. It is not known if the mogrosides themselves or associated components in the extract were the cause of this effect.

Regulatory Status

The use of monk fruit in China has a long history. It is approved for use in China, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong. It is commonly used in South Korea and Malaysia. Australia and New Zealand approved its use as a dietary supplement.

In the USA, juice and a dried concentrate from the monk fruit have GRAS status, granted in 2010. It is generally labelled as lo han guo fruit concentrate or monk fruit concentrate.

In the EU, monk fruit is not permitted as a sweetener although it is described as a natural flavour preparation but at concentrations where it does not function as a sweetener. There are a number of suppliers seeking EU approval for both the juice concentrate and the powder as a food additive.

Leave a Reply