Hypopituitarism is a complex endocrine disorder defined by the partial or complete deficiency of one or more hormones produced by the anterior pituitary gland. The pituitary, often referred to as the “master gland,” occupies a central role in regulating multiple endocrine axes by secreting trophic hormones that stimulate downstream endocrine glands, such as the thyroid, adrenal cortex, gonads, and, indirectly, tissues involved in growth and lactation. Because of its central position in the hypothalamic–pituitary–endocrine network, dysfunction of the pituitary has widespread systemic consequences. In hypopituitarism, insufficient production of pituitary hormones leads not only to low circulating levels of those hormones themselves but also to reduced stimulation of downstream endocrine organs, culminating in secondary hormone deficiencies. Understanding the pathophysiology of hypopituitarism, its causes, and its systemic effects requires a detailed appreciation of endocrine physiology, feedback regulation, and the interdependence of hormonal axes.

Anatomy and Function of the Pituitary Gland

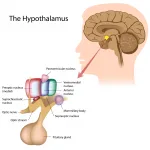

The pituitary gland is a small, pea-sized structure located within the sella turcica of the sphenoid bone at the base of the brain, immediately inferior to the hypothalamus. It consists of two primary lobes: the anterior lobe (adenohypophysis) and the posterior lobe (neurohypophysis). The anterior pituitary is responsible for producing and secreting a variety of peptide hormones under the control of hypothalamic releasing and inhibiting factors delivered via the hypothalamo–hypophyseal portal system. These hormones include adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), growth hormone (GH), and prolactin (PRL). Each of these hormones plays a distinct role in regulating subordinate endocrine organs: ACTH stimulates cortisol production in the adrenal cortex, TSH drives thyroid hormone synthesis in the thyroid gland, LH and FSH control sex steroid production and gametogenesis in the gonads, GH affects growth and metabolism both directly and via insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) produced in the liver, and prolactin regulates lactation. The posterior pituitary stores and releases antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and oxytocin, although these hormones are synthesized in the hypothalamus.

Hypopituitarism most commonly affects the anterior pituitary. Deficiency may be isolated, involving a single hormone, or panhypopituitarism, involving multiple anterior pituitary hormones. The etiology is heterogeneous, ranging from tumors and vascular lesions to inflammatory, infectious, traumatic, or genetic causes.

Etiology of Hypopituitarism

Understanding the consequences of hypopituitarism requires considering its diverse causes. Pituitary adenomas, benign tumors of pituitary cells, are the most frequent cause of adult hypopituitarism. Macroadenomas may compress normal pituitary tissue, causing progressive loss of hormone secretion. Craniopharyngiomas, particularly in children, and other hypothalamic tumors can also impair pituitary function by compressive or infiltrative mechanisms. Sheehan’s syndrome, postpartum necrosis of pituitary tissue due to severe hemorrhage, results in abrupt loss of anterior pituitary function, exemplifying vascular causes. Traumatic brain injury and surgical or radiotherapeutic interventions targeting the pituitary can similarly produce hypopituitarism. Less commonly, autoimmune hypophysitis, infiltrative disorders (such as sarcoidosis or hemochromatosis), infections, or genetic mutations affecting pituitary development can underlie the condition. Regardless of etiology, the hallmark is a reduction in pituitary hormone output, which translates into a cascade of downstream endocrine deficiencies.

Hormonal Consequences in the Blood

Hypopituitarism leads to two primary biochemical consequences: diminished levels of circulating pituitary hormones and corresponding decreases in the hormones produced by subordinate endocrine glands. These consequences are mediated both directly by the absence of trophic stimulation and indirectly through altered feedback mechanisms.

1. Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) Deficiency

ACTH stimulates the adrenal cortex, particularly the zona fasciculata, to produce glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol. In ACTH deficiency, circulating cortisol levels fall, resulting in secondary adrenal insufficiency. Clinically, this manifests as fatigue, hypotension, hypoglycemia, weight loss, and impaired stress tolerance. Unlike primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease), hyperpigmentation is absent because ACTH levels are low rather than elevated, preventing excessive melanocortin receptor stimulation in the skin. In laboratory tests, patients show low cortisol levels with inappropriately low ACTH levels, reflecting the central origin of the deficiency. Pharmacologically, the situation mirrors chronic adrenal glucocorticoid withdrawal, and treatment requires replacement with hydrocortisone or another glucocorticoid, titrated carefully to avoid over- or under-replacement.

2. Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) Deficiency

TSH produced by thyrotrophs of the anterior pituitary stimulates the thyroid gland to synthesize and release thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Hypopituitarism affecting TSH leads to secondary hypothyroidism, characterized by low thyroid hormone levels in the blood despite low or inappropriately normal TSH. The lack of TSH stimulation results in reduced thyroid hormone synthesis, decreased basal metabolic rate, cold intolerance, bradycardia, constipation, weight gain, and lethargy. Importantly, the thyroid gland itself is structurally normal but under-stimulated, distinguishing secondary hypothyroidism from primary thyroid failure, where TSH is elevated due to negative feedback from low thyroid hormones.

3. Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) Deficiency

Gonadotropins LH and FSH are essential for normal gonadal function. LH stimulates testosterone production in Leydig cells in males and ovulation in females, while FSH promotes spermatogenesis and follicular development. Hypopituitarism causes secondary hypogonadism, with low testosterone or estradiol levels and inappropriately low or normal gonadotropin concentrations. Clinically, this leads to reduced libido, erectile dysfunction in men, amenorrhea and infertility in women, and impaired secondary sexual characteristics in adolescents. Gonadal tissue itself may be capable of hormone production but is functionally quiescent due to lack of pituitary stimulation.

4. Growth Hormone (GH) Deficiency

GH, secreted by somatotrophs, regulates somatic growth and metabolism. GH acts directly on tissues and indirectly via IGF-1 production in the liver. In children, GH deficiency causes growth retardation, delayed skeletal maturation, and proportionate short stature. In adults, GH deficiency is associated with altered body composition, increased fat mass (particularly visceral), reduced muscle mass, decreased exercise capacity, and impaired quality of life. Laboratory testing reveals low IGF-1 levels, which reflect diminished GH action, and blunted GH responses to stimulation tests. GH deficiency illustrates how pituitary hormone deficits can exert profound effects even when peripheral organs remain structurally normal.

5. Prolactin (PRL) Deficiency

Prolactin deficiency, although less clinically critical than deficiencies of ACTH, TSH, GH, or gonadotropins, may impair lactation in postpartum women. Prolactin normally promotes milk synthesis in mammary alveolar cells, and its deficiency results in failure to initiate or maintain lactation. This effect exemplifies the dependence of peripheral endocrine tissue on pituitary trophic hormones.

Mechanisms of Reduced Hormone Production in Subordinate Endocrine Organs

The reduced hormone levels in peripheral endocrine glands are primarily due to the loss of trophic stimulation from pituitary hormones. Unlike primary gland disorders, where the peripheral organ itself is dysfunctional, secondary or tertiary endocrine deficiencies stem from insufficient signaling. This results in several pathophysiological consequences:

-

Atrophy of the target gland: Without chronic stimulation by trophic hormones, endocrine organs often undergo structural involution. For example, chronic ACTH deficiency leads to atrophy of the adrenal cortex; chronic TSH deficiency results in thyroid gland shrinkage.

-

Functional quiescence: Enzymes responsible for hormone biosynthesis are downregulated in the absence of stimulating signals. Steroidogenic enzymes in the adrenal cortex, thyroid peroxidase, and aromatase in gonadal tissue are all sensitive to trophic input.

-

Feedback dysregulation: Normally, low levels of peripheral hormones trigger negative feedback that increases pituitary output. In hypopituitarism, this compensatory mechanism is ineffective because the pituitary itself is incapable of mounting an appropriate response. Thus, low cortisol, thyroid hormones, or sex steroids persist despite the body’s homeostatic needs.

-

Downstream metabolic consequences: Peripheral organs cannot compensate for systemic hormonal deficits. For example, impaired cortisol synthesis compromises glucose homeostasis and stress response; reduced thyroid hormone production diminishes basal metabolic rate and cardiovascular function; gonadal hormone deficiency affects fertility and secondary sexual characteristics.

Clinical Manifestations

Hypopituitarism presents with a constellation of symptoms reflecting the combined effects of multiple hormone deficiencies. The clinical picture may be subtle and gradual in onset, especially in adult patients with slowly enlarging pituitary tumors. Fatigue, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, hypotension, and cold intolerance are common. Menstrual irregularities, erectile dysfunction, and infertility are frequently reported. Children may present with growth failure, while adults exhibit altered body composition and decreased exercise tolerance. Importantly, the sequence of hormonal loss can follow a characteristic pattern: GH is often the first to decline, followed by gonadotropins, TSH, and finally ACTH. This sequence has implications for diagnosis and management. In some cases, sudden pituitary failure, such as after hemorrhage (Sheehan’s syndrome) or pituitary apoplexy, can produce acute adrenal insufficiency, a life-threatening emergency.

Diagnostic Considerations

Diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical suspicion, biochemical testing, and imaging. Hormone assays reveal low levels of pituitary hormones and correspondingly low levels of peripheral hormones in secondary deficiencies. Stimulation tests may be used to assess reserve capacity, such as ACTH stimulation for adrenal function or GH stimulation tests. MRI imaging identifies structural lesions of the pituitary or hypothalamus. Understanding the pattern of hormone loss and feedback relationships is critical for distinguishing hypopituitarism from primary gland failure.

Treatment Strategies

Management of hypopituitarism centers on hormone replacement therapy tailored to the specific deficiencies. Glucocorticoids are administered to replace cortisol, levothyroxine for thyroid hormone deficiency, sex steroids (testosterone or estrogen/progesterone) for gonadal insufficiency, and GH replacement when indicated. Careful sequencing is essential; for example, glucocorticoid replacement must precede thyroid hormone therapy in ACTH-deficient patients to avoid precipitating adrenal crisis. Monitoring therapy involves periodic measurement of hormone levels, assessment of clinical response, and adjustment of doses over time. In cases where a pituitary lesion is responsible, surgical removal, radiotherapy, or medical therapy may be necessary.

Conclusion

Hypopituitarism exemplifies the profound impact of pituitary dysfunction on systemic physiology. As the “master gland,” the anterior pituitary orchestrates the activity of multiple subordinate endocrine organs, and its failure produces widespread secondary hormone deficiencies. ACTH deficiency leads to adrenal insufficiency, TSH deficiency to secondary hypothyroidism, LH and FSH deficiencies to hypogonadism, GH deficiency to impaired growth and altered metabolism, and prolactin deficiency to lactation failure. The loss of trophic hormone stimulation results in both functional quiescence and atrophy of peripheral glands, with persistent deficits despite normal glandular structure. Clinically, patients present with fatigue, hypotension, growth failure, reproductive disturbances, and metabolic abnormalities. Diagnosis requires careful hormonal assessment, and treatment is based on judicious hormone replacement and, when applicable, correction of the underlying pituitary pathology. Understanding the pathophysiology of hypopituitarism underscores the intricate interdependence of endocrine organs and highlights the central role of the pituitary gland in maintaining systemic hormonal homeostasis.

Leave a Reply