Penicillin is a group of extremely valuable antibiotics which remain commercially important to this day. They are produced by the Penicillium moulds. The main organism of production is Penicillium chrysogenum (Calam et al., 1951).

They include a number of variants; penicillin V (taken orally), penicillin G (taken intravenously), procaine penicillin and benzathine penicillin (taken intramuscularly). They were the first medicines to be effective against a number of deadly bacterial infections such as Streptococci and Staphylococci.

The synthesis of penicillin involves a complex process that combines organic chemistry techniques with microbial fermentation. It relies on culture maintenance, fermentation, and extraction/purification procedures that need careful management.

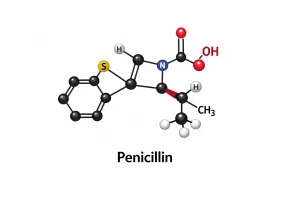

Structure Of Penicillin

-

Penicillin has a β-lactam ring fused to a thiazolidine ring.

-

The β-lactam ring is a four-membered lactam (cyclic amide).

-

The thiazolidine ring is a five-membered ring containing sulfur and nitrogen.

-

The side chain varies depending on the type of penicillin (for penicillin G, it’s a benzyl group attached to the amide of the β-lactam).

Function As An Antibiotic

Penicillin inhibits those enzymes that cross-link peptidoglycans in bacterial cell walls. The result is a weakened cell wall and eventual cell death. Some bacteria have developed resistance to these antibiotics by developing beta-lactamases that break down the beta-lactam ring.

1. Historical Context

-

Penicillin was first discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928 from Penicillium notatum.

-

Early production was limited to small-scale lab cultures. They were widely used during the war to treat sepsis.

-

During World War II, large-scale production was developed using Penicillium chrysogenum strains in deep-tank fermentation, which made mass production possible. The fed-batch process was also developed at this time.

The fermentation substrate has been studied over a number of years. Jarvis and Johnson (1947) made considerable headway on the relationship between sugar utilization and penicillin formation. That study showed the optimum penicillin yield is obtained when the glucose and lactose ratio is such that an appropriate amount of mycelia is formed using any available glucose before the mould reverts to a slower form of fermentation using lactose.

A couple of years later Cook and Brown from 1949 onwards assessed the affects of of different carbohydrates and salts on antibiotic yield. Glucose is the preferred substrate for growth although it inhibits penicillin production. Lactose is then fed into the fermenter for optimal antibiotic production as it does not inhibit its production (Soltero & Johnson, 1953).

The conventional industrial method has largely been based on the fed-batch approach. The cells need to be stressed for optimal penicillin production. In keeping with secondary metabolite production, when fungal growth is compromised then such compounds are produced to a great extent. During the growth phase there is no penicillin production (Calam et al., 1951; Camici et al., 1952;

The synthetic pathway is:-

alpha-ketoglutarate –> AcetylCo A—> homocitrate–>L-alpha-aminoadipic acid –>L-lysine + beta-lactam

L-lysine inhibits production of homocitrate and needs to be removed if possible during fermentation otherwise it stops penicillin production through feedback inhibition.

2. Microbial Production

Organism

-

Industrial penicillin is produced by the mold Penicillium chrysogenum.

-

Strains are genetically improved to enhance yield and reduce unwanted byproducts.

Inoculum Preparation

-

Pure spores are grown stepwise in sterile seed cultures.

-

This ensures a healthy, active culture for large-scale fermentation.

Fermentation Process

-

Large stainless-steel fermenters are used – upto 100 thousand gallons but usually in parallel systems of 50 thousand gallons.

-

Medium contains:

-

Carbon sources: glucose (initially), lactose (later added for optimal penicillin production). Other crude sugars have been examined. Industrial wastes such as sugar cane bagasse (SCB) and corn steep liquor have been used with success.

-

Nitrogen sources: corn steep liquor, ammonium salts

-

Mineral salts and precursors like phenylacetic acid (for penicillin G). The pH, levels of nitrogen, phosphates, amino acids such as lysine and oxygen concentration are carefully managed. Sugar also regulates pH during fermentation especially during the full growth phase when penicillin production is maximal.

-

-

Conditions are carefully controlled:

-

Aeration and agitation for oxygen supply

-

Temperature around 25–27°C

-

pH around 6.5

-

-

Penicillin is secreted into the culture medium towards the end of growth phase as glucose begins to run out.

3. Extraction and Purification

-

The mycelium is removed by filtration or centrifugation and often further washed to recover antibiotic and then used as animal feed..

-

Penicillin is sensitive to pH; extraction uses:

-

Acidification or alkalization of the broth. Acidification is preferred and claimed to be better on whole broth rather than refined broth. The main issue is to reduce the amount of time the penicillin spends in an acidic pH as it is more unstable.

-

Solvent extraction -organic solvents like amyl acetate, butyl acetate and isobutyl acetate are used

-

Potassium salts are added to precipitate the penicillin in the solvent.

-

Back-extraction into an aqueous phase

-

-

Further work-up may also require crystallization or salt formation (e.g., sodium or potassium penicillin).

4. Semi-Synthetic Penicillins

-

To expand the spectrum of activity or improve stability, 6-aminopenicillanic acid (6-APA), obtained from fermentation, is chemically modified.

-

Example derivatives:

-

Ampicillin

-

Amoxicillin

-

Methicillin

-

This hybrid method combines biological fermentation and chemical synthesis.

5. Formulation and Quality Control

-

Purified penicillin is sterilized and formulated into:

-

Tablets or capsules

-

Injectable solutions

-

Powders for reconstitution

-

-

Stringent quality control ensures:

-

Purity

-

Correct dosage

-

Stability

-

6. Key Considerations

-

Penicillin is unstable in acidic conditions, requiring careful handling.

-

Production efficiency relies on:

-

High-yield fungal strains

-

Optimized fermentation media and conditions

-

Effective extraction and purification methods

-

Penicillin Manufacture And Fermentation Modelling

Penicillin manufacture is a good model for fermentation processes and purification. It is a very well researched example of secondary metabolite production and continues to this day to provide insights on the production of other metabolites, especially those that are manufactured extracellularly.

Production has been explored by both academia and business alike. Batch fermentation is extremely common in secondary metabolite production. Constantinides et al., (1970a & b) developed two types of mathematical models for this purpose. These were general models that were based on averaged, nondimensionalized cell and penicillin synthesis curves. The other were models based on experimental information. Interestingly, these studies of fermentation compare fermentation at constant temperature conditions with variable temperature conditions.

Bajpal and Reuss (1980) developed a mechanistic model of a fed-batch fermentation for penicillin production. They applied Contois growth kinetics coupled to a substrate-inhibition model for product formation. The growth media was corn steep liquor and synthetic chemicals. Experimentally, they were able to investigate the effects of initial sugar concentrations, the feeding rate and the volumetric mass transfer coefficient for oxygen (KLa) .

Costing A Penicillin Process

A number of factors affect the cost of penicillin production. The cost of producing Penicillin G (benzylpenicillin) for example via fermentation can vary significantly based on factors such as production scale, geographic location, raw material costs, and operational efficiencies. Over the years, the capital cost of fermentation has changed because the age of the facility including the fermenter itself changes over time. Many large-scale facilities are over 20 years old now and these fixed charges are reduced significantly unless rebuilding is required (Swartz, 1979). While specific per-kilogram production costs are not readily available in any of the academic sources, we can glean some insights from what data is available.

It’s important to note that the synthesis of penicillin involves several variations and modifications based on the specific type of penicillin being produced. Additionally, advances in biotechnology have allowed for genetic engineering techniques to enhance the production of penicillin by optimizing the fungal strains used in fermentation and improving the overall yield of the process.

Market Pricing and Production Costs

-

Market Price: As of late 2024, the price of Penicillin G Sodium in China reached approximately USD 46,000 per metric ton (or USD 46 per kilogram), influenced by supply constraints and increased demand.

Production Costs: While exact figures are not specified, the production cost of Penicillin G is influenced by several factors such as:

-

Raw Materials: Costs for substrates like glucose, corn steep liquor, and phenylacetic acid.

-

Utilities: Energy consumption for fermentation and downstream processing.

-

Labour and Overheads: Operational labour, maintenance, and quality control.

-

Capital Expenditures: Investment in fermentation equipment and facility infrastructure.

Capital Investment Considerations

-

Plant Setup Costs: Establishing a Penicillin G production facility with an annual capacity of 625 tonnes may require an investment ranging from USD 5 million to USD 52 million, depending on factors like location, technology, and scale.

-

Operational Factors: The fermentation process typically spans 120 to 200 hours, with additional time allocated for downstream processing.

Market Dynamics and Challenges

-

Pricing Pressures: Historical data indicates that Penicillin G prices have experienced volatility. For instance, in 2004, prices dropped to USD 6 per billion units, leading some manufacturers to reconsider their involvement in the market due to unviable profit margins.

-

Supply and Demand: Factors such as global demand, raw material availability, and geopolitical events can significantly impact both production costs and market prices.

While exact production costs per kilogram of Penicillin G are not specified in the available sources, market prices as of late 2024 suggest a selling price of approximately USD 46 per kilogram. Producers must consider various factors, including raw material costs, operational expenses, and capital investments, to determine profitability. Given the complexities and market dynamics, it’s essential for manufacturers to conduct detailed feasibility studies tailored to their specific circumstances.

Penicillin production is essentially a microbial fermentation process, optimized over decades, followed by careful extraction and purification. While chemical synthesis of penicillin itself is impractical, fermentation combined with chemical modification enables the creation of semi-synthetic penicillins, broadening therapeutic applications.

This process highlights the intersection of biotechnology, microbiology, and pharmaceutical engineering in producing life-saving antibiotics.

References

Bajpai, R. K., & Reuss, M. (1980). A mechanistic model for penicillin production. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology, 30(1), pp. 332-344 (Article).

Brewer Jr, G. A., & Johnson, M. J. (1953). Activity and properties of para-aminobenzyl penicillin. Applied Microbiology, 1(4), pp. 163-166.

Calam, C. T., Driver, N., & Bowers, R. H. (1951). Studies in the production of penicillin, respiration and growth of Penicillium chrysogenum in submerged culture, in relation to agitation and oxygen transfer. Journal of Applied Chemistry, 1(5), pp. 209-216 (Article).

Camici, L., Sermonti, G., & Chain, E. B. (1952). Observations on Penicillium chrysogenum in submerged culture: 1. Mycelial growth and autolysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 6(1-2), pp. 265.

Constantinides, A., Spencer, J. L., & Gaden Jr, E. L. (1970a). Optimization of batch fermentation processes. II. Optimum Temperature Profiles for Batch Penicillin Fermentations. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 12(5), pp. 1081-1098

Constantinides, A., Spencer, J. L., & Gaden Jr, E. L. (1970b). Optimization of batch fermentation processes. II. Development of mathematical models for batch penicillin fermentations. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 12(5), pp. 803-830 .

Cook, R. P. and Brown, M. B. (1949-50) Studies in penicillin formation. Proc. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh, MB, pp. 137-71.

Elander, R. P. (2003). Industrial production of β-lactam antibiotics. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 61(5), pp. 385-392.

Hosler, P., & Johnson, M. J. (1953). Penicillin from chemically defined media. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry, 45(4), pp. 871-874. .

Jarvis, F. G., & Johnson, M. J. (1947). The Role of the Constituents of Synthetic Media for Penicillin Production1. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 69(12), pp. 3010-3017

Jarvis, F. G., & Johnson, M. J. (1950). The mineral nutrition of Penicillium chrysogenum Q176. Journal of Bacteriology, 59(1), pp. 51-60.

Soltero, F. V., & Johnson, M. J. (1953). The effect of the carbohydrate nutrition on penicillin production by Penicillium chrysogenum Q-176. Applied Microbiology, 1(1), pp. 52-57.

Swartz, R. W. (1979). The use of economic analysis of penicillin G manufacturing costs in establishing priorities for fermentation process improvement. In Annual Reports on Fermentation Processes (Vol. 3, pp. 75-110). Elsevier

Another great article. I recommend you to my colleagues on the course.