Genome sequencing is the process of determining the complete DNA sequence of an organism’s genome, encompassing all of its genes and non-coding regions. Since the first complete genome of a free-living organism was sequenced in 1995, genome sequencing has become a foundational technology in modern biology, medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology. Advances in sequencing methods have dramatically reduced cost and time while increasing accuracy and throughput, transforming genome sequencing from a monumental scientific achievement into a routine laboratory procedure. Understanding the methods used in genome sequencing is essential for appreciating both the power and limitations of genomic data.

Early DNA Sequencing Methods

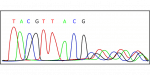

The earliest widely used method for DNA sequencing was the Sanger sequencing method, developed by Frederick Sanger in 1977. This technique, also known as chain-termination sequencing, relies on DNA polymerase to synthesize a complementary strand of DNA in the presence of normal nucleotides and modified nucleotides called dideoxynucleotides. Incorporation of a dideoxynucleotide terminates DNA synthesis, producing fragments of varying lengths that end at each nucleotide position. These fragments are separated by electrophoresis, allowing the DNA sequence to be read.

Sanger sequencing is highly accurate and produces relatively long reads, typically up to 800–1000 base pairs. However, it is labour-intensive, low-throughput, and expensive when applied to large genomes. For this reason, while Sanger sequencing played a critical role in early genome projects such as the Human Genome Project, it has largely been replaced by high-throughput sequencing technologies for whole-genome sequencing, although it is still used for validation and small-scale sequencing tasks.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

The development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies in the mid-2000s revolutionized genome sequencing by enabling the parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments. NGS platforms share several common steps: DNA fragmentation, library preparation, sequencing, and computational assembly. However, they differ in chemistry, read length, accuracy, and output.

One of the most widely used NGS platforms is Illumina sequencing, which operates on the principle of sequencing by synthesis. In this method, fragmented DNA is attached to a flow cell and amplified into clusters through bridge amplification. During sequencing, fluorescently labeled nucleotides are incorporated one base at a time, and a camera records the emitted fluorescence to determine the nucleotide identity. Illumina platforms produce short reads, typically ranging from 50 to 300 base pairs, but with very high accuracy and massive throughput.

One term that is often used is contig. This is a contiguous stretch of DNA sequence that is a assembled from overlapping reads. A contig however does not necessarily represent a complete chromosome.

Illumina sequencing has become the standard for many applications, including whole-genome sequencing, RNA sequencing, and metagenomics. Its main limitation lies in the short read length, which makes it difficult to resolve repetitive regions, structural variations, and complex genomic rearrangements. As a result, Illumina-based genome assemblies are often fragmented into multiple contigs, particularly for large or repeat-rich genomes.

Another early NGS technology was 454 pyrosequencing, which detected nucleotide incorporation through the release of light generated by enzymatic reactions. Although it produced longer reads than early Illumina platforms, 454 sequencing was costly and prone to errors in homopolymer regions. It has since been discontinued but played an important transitional role in the evolution of sequencing technologies.

Third-Generation (Long-Read) Sequencing

To overcome the limitations of short-read sequencing, third-generation sequencing technologies were developed. These platforms sequence individual DNA molecules directly and generate much longer reads, often exceeding 10,000 base pairs. Two prominent examples are Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT).

PacBio sequencing uses single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing, in which DNA polymerase synthesizes a complementary strand while fluorescently labeled nucleotides are detected in real time. The key advantage of PacBio sequencing is its ability to produce long reads that span repetitive regions and structural variants, enabling more contiguous genome assemblies. Although raw PacBio reads have a higher error rate than Illumina reads, these errors are largely random and can be corrected by high sequencing coverage or by combining PacBio data with short-read data.

Oxford Nanopore sequencing takes a different approach, passing single DNA molecules through nanopores embedded in a membrane. Changes in ionic current as nucleotides pass through the pore are measured and translated into sequence information. Nanopore sequencing offers ultra-long reads, sometimes exceeding hundreds of kilobases, and allows real-time data generation with portable devices. However, it currently has lower per-base accuracy than Illumina, although continuous improvements in chemistry and software are narrowing this gap.

Genome Assembly Strategies

Sequencing alone does not yield a complete genome; the raw reads must be computationally assembled into a coherent sequence. Two major assembly strategies are used: reference-based assembly and de novo assembly.

Reference-based assembly aligns sequencing reads to an existing reference genome. This approach is computationally efficient and accurate when a closely related reference genome is available. However, it can miss novel sequences, structural variations, or genome rearrangements that differ from the reference.

De novo assembly, by contrast, constructs a genome without relying on a reference. This method is essential for sequencing new species or highly divergent strains. Short-read assemblers often use de Bruijn graphs, while long-read assemblers rely on overlap-layout-consensus approaches. De novo assembly is more challenging but provides a more complete and unbiased representation of the genome.

Hybrid Sequencing Approaches

Modern genome sequencing projects often use hybrid approaches, combining short-read and long-read data. Short reads provide high base-level accuracy, while long reads resolve structural complexity and repetitive regions. By integrating both data types, researchers can produce highly accurate, contiguous genome assemblies. This strategy is commonly used in microbial genomics, plant genomics, and medical research.

Real-World Example

An example of a modern genome sequencing activity was that of the bacterium Pseudomonas brassicacearum strain DF41. The study was written up in 2014 but provides a good example of best practice in genome sequencing (Loewen et al., 2014). The genome of this bacterium was obtained in two stages and demonstrates how different technologies and data sets can be used sequentially to improve the final genome assembly.

In the first stage, the researchers generated raw DNA sequence data using an Illumina MiSeq platform. Illumina MiSeq is a typical next-generation sequencing machine of the sort we have already referenced that produces millions of short DNA reads, typically a few hundred base pairs long. These reads are accurate but short, which means they cannot directly reveal the entire genome sequence without further computational processing.

Because the sequencing output consists of many short fragments, the researchers then used genome assembly software to reconstruct longer stretches of DNA by identifying overlaps between reads. Specifically, they used a combination of three bioinformatics tools:

-

MIRA Assembler (version 3.9.3), which is designed for assembling short-read sequencing data and is often used for microbial genomes.

-

Velvet (version 1.2.08), a de Bruijn graph–based assembler that efficiently assembles short Illumina reads into longer sequences.

-

MUMmer (version 3.23), which is primarily a sequence alignment tool; here it was likely used to compare, refine, or merge assemblies produced by MIRA and Velvet, helping to resolve overlaps or inconsistencies.

The result of this assembly process was 298 contigs. The fact that the genome was assembled into 298 contigs indicates that the genome was fragmented at this stage, meaning gaps remained between assembled regions due to repetitive sequences, insufficient coverage, or limitations of short-read sequencing.

In its simplest terms, the statement means that the researchers first used Illumina MiSeq sequencing to generate short DNA fragments from the bacterium’s genome, then used multiple software tools to piece those fragments together into longer DNA sequences. After this initial effort, they were able to reconstruct the genome only partially, resulting in 298 separate DNA segments, which is why a second sequencing stage was needed later to improve completeness.

In the second phase, the researcher completed and validated the genome assembly using a different sequencing technology.

The researchers used the dataset produced by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) sequencing. It’s worth just reminding ourselves that PacBio sequencing differs fundamentally from Illumina sequencing in that it generates much longer DNA reads—often tens of thousands of base pairs long—although individual reads have a higher raw error rate. These long reads are especially valuable for resolving repetitive regions and closing gaps that short reads cannot span. The sequencing itself was carried out by Genome Québec, a specialized genomics facility, indicating that the data were generated by a professional sequencing center rather than in-house.

The PacBio data were assembled using the PacBio SMRT Analysis pipeline (version 2.0.1). This is PacBio’s dedicated software suite designed specifically to assemble long-read data. Because the reads are long, the assembler can often reconstruct entire chromosomes without breaks, provided the sequencing depth is sufficient.

The phrase “222× coverage” means that, on average, each position in the genome was sequenced 222 times. This is extremely high coverage and is important for PacBio sequencing because it allows the software to correct random sequencing errors by comparing many reads covering the same region. High coverage therefore increases both the accuracy and completeness of the final genome assembly.

As a result of this process, the researchers obtained a single contiguous genome sequence. This means the entire bacterial chromosome was assembled into one continuous DNA sequence with no gaps, often referred to as a closed genome. Achieving a single contig is a major improvement over the earlier Illumina-based assembly, which consisted of 298 separate contigs.

For validation,the researchers used the previously generated Illumina contigs as an independent check. They aligned those short-read assemblies against the PacBio-derived genome to verify that the sequences matched and that no major errors, rearrangements, or missing regions were present. Because Illumina reads are highly accurate at the base-pair level, this alignment step increases confidence in the correctness of the final PacBio assembly. So what happened then was the researchers used long-read PacBio sequencing with very high coverage to close all the gaps and assemble the genome into one complete sequence, then cross-checked that result using the earlier Illumina-based data to confirm its accuracy and reliability.

What we have here is a good example of genome sequencing using the current thinking and tools available.

Applications and Future Directions

Genome sequencing has applications across many fields, including disease diagnosis, evolutionary biology, agriculture, and environmental science. In medicine, genome sequencing enables precision medicine by identifying disease-associated mutations. In agriculture, it supports crop improvement and disease resistance. In ecology, it allows the study of microbial communities and biodiversity.

Future developments in genome sequencing are focused on increasing read accuracy, reducing cost, and simplifying data analysis. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, genome sequencing will become even more accessible, enabling deeper insights into the structure, function, and evolution of genomes.

Genome sequencing has progressed from laborious, low-throughput methods to highly automated, high-resolution technologies capable of sequencing entire genomes rapidly and accurately. Each sequencing method—Sanger, short-read NGS, and long-read third-generation platforms—has distinct strengths and limitations, making them suitable for different applications. The continued refinement of sequencing methods and assembly strategies ensures that genome sequencing remains a central tool in biological research, shaping our understanding of life at its most fundamental level.

References

Loewen, P. C., Switala, J., Fernando, W. D., & de Kievit, T. (2014). Genome sequence of Pseudomonas brassicacearum DF41. Genome Announcements, 2(3), pp.10-1128. .

Leave a Reply