Cushing’s disease, a clinical syndrome characterized by chronic exposure to elevated levels of glucocorticoids, represents one of the most striking examples of how hormonal imbalance can profoundly affect nearly every organ system in the body. Although the condition is classically defined as hypercortisolism due to an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)–secreting pituitary adenoma, the term “Cushing’s syndrome” more broadly encompasses all causes of excess cortisol, whether of endogenous origin (such as adrenal tumors or ectopic ACTH production) or exogenous origin, most notably prolonged therapeutic use of synthetic glucocorticoids. Regardless of the underlying cause, the clinical presentation reflects the diverse and potent physiological actions of cortisol on metabolism, connective tissue, immune regulation, cardiovascular function, and central nervous system activity. This essay will explore the characteristic symptoms and signs of Cushing’s disease, and systematically explain them in light of the known pharmacological and physiological effects of glucocorticoids.

The Role of Cortisol in Normal Physiology

Cortisol is the primary glucocorticoid produced by the adrenal cortex in humans, secreted under the control of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. It plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis during stress, regulating metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, and modulating immune and inflammatory responses. Cortisol also influences vascular tone, bone metabolism, and central nervous system function. Its actions are mediated by intracellular glucocorticoid receptors that, upon ligand binding, regulate transcription of numerous target genes. In pharmacology, synthetic glucocorticoids such as prednisolone, dexamethasone, and hydrocortisone exploit these same receptor-mediated pathways, producing powerful anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects. When cortisol or synthetic glucocorticoid levels remain elevated for prolonged periods, however, the same mechanisms that are adaptive in acute stress become maladaptive, producing the constellation of features seen in Cushing’s syndrome.

Characteristic Symptoms and Their Physiological Basis

1. Changes in Body Fat Distribution

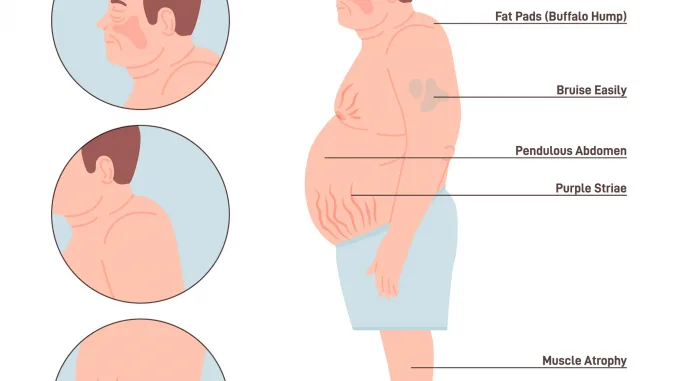

One of the hallmark signs of Cushing’s disease is the development of central or truncal obesity, often accompanied by a rounded “moon face” and a “buffalo hump” of fat deposition in the supraclavicular and dorsocervical regions. These features contrast with relatively thin limbs. The underlying mechanism relates to cortisol’s effects on adipose tissue metabolism. Cortisol promotes lipolysis in peripheral fat stores, particularly in the limbs, releasing free fatty acids into the circulation. At the same time, it facilitates lipogenesis and fat storage in visceral and truncal depots, likely through synergistic actions with insulin and differential sensitivity of adipocytes in various regions. The net result is redistribution of body fat, with characteristic obesity in the trunk, face, and neck, while the extremities appear wasted.

2. Muscle Weakness and Wasting

Patients with Cushing’s often report proximal muscle weakness, difficulty climbing stairs, or rising from a seated position. This is explained by the catabolic effects of glucocorticoids on protein metabolism. Cortisol stimulates proteolysis in skeletal muscle, breaking down muscle proteins into amino acids that are then used by the liver for gluconeogenesis. While this process is useful in stress adaptation, chronic proteolysis leads to muscle atrophy and weakness. In addition, reduced protein synthesis further impairs muscle maintenance and repair. Pharmacologically, this catabolic effect is also observed with long-term steroid therapy, where steroid-induced myopathy can become a debilitating adverse effect.

3. Skin Changes: Thin Skin, Striae, and Easy Bruising

Cushing’s syndrome is notable for its cutaneous manifestations, including thin, fragile skin that bruises easily, poor wound healing, and the presence of purple abdominal striae. These changes are again linked to glucocorticoid-induced protein catabolism. Cortisol reduces fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis, weakening the structural integrity of the dermis. Loss of dermal collagen results in thinning of the skin and makes underlying blood vessels more vulnerable to rupture, producing easy bruising. The reduced tensile strength of skin also explains the wide, violaceous striae, particularly on the abdomen, breasts, and thighs, where stretching forces are greatest. In pharmacology, patients on long-term corticosteroid therapy frequently develop similar dermal thinning and impaired wound healing.

4. Osteoporosis and Skeletal Effects

Another important consequence of chronic cortisol excess is osteoporosis, leading to increased risk of fractures, particularly of the vertebrae, ribs, and hips. Cortisol interferes with bone homeostasis through multiple mechanisms. It decreases osteoblast activity and survival, thereby reducing bone formation, while simultaneously enhancing osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. Glucocorticoids also impair calcium absorption in the gut and increase renal calcium excretion, resulting in negative calcium balance and secondary hyperparathyroidism, which further accelerates bone loss. This is why corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis is one of the most feared complications of long-term glucocorticoid therapy, often necessitating prophylactic measures such as calcium and vitamin D supplementation or bisphosphonate treatment.

5. Glucose Intolerance and Diabetes Mellitus

Cortisol is a potent “diabetogenic” hormone. It stimulates hepatic gluconeogenesis and reduces glucose uptake in peripheral tissues by antagonizing insulin action. The result is increased fasting glucose levels and postprandial hyperglycemia. In susceptible individuals, prolonged hypercortisolism precipitates secondary diabetes mellitus, with classical symptoms of polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia. Pharmacologically, this mechanism underlies the well-recognized risk of glucocorticoid-induced diabetes in patients receiving chronic corticosteroid therapy. This also explains why glycemic control can be challenging in diabetic patients requiring steroid treatment for inflammatory or autoimmune conditions.

6. Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disturbances

Patients with Cushing’s frequently develop hypertension, dyslipidemia, and increased cardiovascular risk. Cortisol contributes to hypertension through several pathways: it enhances vascular responsiveness to catecholamines and angiotensin II, increases renal sodium and water retention by binding mineralocorticoid receptors (especially at high concentrations), and stimulates renin-angiotensin system activity. Dyslipidemia arises from increased lipolysis, altered lipid transport, and hepatic overproduction of very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL). Together, these changes accelerate atherosclerosis, explaining why cardiovascular disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in Cushing’s syndrome. These same mechanisms are evident in patients on long-term corticosteroid therapy, where hypertension and dyslipidemia are common side effects.

7. Immune Suppression and Susceptibility to Infection

Glucocorticoids are among the most potent immunosuppressive agents known, which explains their wide use in treating inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. However, in Cushing’s disease, the same pharmacological effect becomes pathological. Cortisol inhibits the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, suppresses T-cell proliferation, reduces macrophage activation, and decreases neutrophil migration into tissues. While this dampens harmful inflammation, it also leaves patients susceptible to opportunistic infections, including bacterial, viral, and fungal pathogens. Wound healing is impaired, and the risk of sepsis is elevated. In addition, reactivation of latent infections such as tuberculosis may occur. Clinically, this immunosuppressive state mirrors the adverse effects seen in patients on chronic steroid therapy.

8. Neuropsychiatric Disturbances

The central nervous system is highly sensitive to glucocorticoid levels, and patients with Cushing’s disease often experience mood disturbances, cognitive impairment, and sleep problems. Depression, irritability, anxiety, and even psychosis have been reported. The underlying mechanisms involve glucocorticoid modulation of neurotransmitter systems, hippocampal function, and circadian rhythms. Chronic cortisol excess can impair hippocampal neurogenesis and contribute to memory deficits. Sleep disturbances are linked to disruption of the diurnal cortisol rhythm, as normal circadian regulation is lost in Cushing’s. Pharmacologically, long-term corticosteroid therapy is well known to induce mood swings, insomnia, and in some cases severe psychiatric symptoms referred to as “steroid psychosis.”

9. Reproductive and Endocrine Effects

Glucocorticoid excess disrupts the normal hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. In women, menstrual irregularities, amenorrhea, and infertility are common. In men, hypogonadism and decreased libido may occur. These effects are due to cortisol-mediated suppression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and gonadotropin secretion, combined with direct inhibition of gonadal steroidogenesis. In children, excessive cortisol can impair growth by inhibiting growth hormone secretion and directly affecting the growth plate. Similarly, pharmacological glucocorticoid therapy is a known cause of growth retardation in pediatric patients.

10. Other Features: Hirsutism, Acne, and Skin Pigmentation

In ACTH-dependent Cushing’s disease, excess ACTH stimulates adrenal androgen production, leading to hirsutism and acne in women. This is particularly prominent in pituitary-driven hypercortisolism. Hyperpigmentation may also occur in ectopic ACTH syndrome, as high ACTH levels cross-react with melanocortin receptors in the skin. While these features are less directly linked to glucocorticoid pharmacology, they represent important clinical manifestations of the disease.

Exogenous Glucocorticoids as a Cause of Cushing’s Syndrome

While endogenous hypercortisolism is relatively rare, the most common cause of Cushing’s syndrome in clinical practice is iatrogenic, resulting from prolonged therapeutic administration of synthetic glucocorticoids. These drugs mimic cortisol’s actions, producing the same metabolic, musculoskeletal, dermatological, and psychiatric complications described above. Because synthetic glucocorticoids often have greater potency and longer duration of action than endogenous cortisol, their adverse effects can be even more pronounced. Furthermore, chronic exogenous glucocorticoid use suppresses the HPA axis via negative feedback, leading to adrenal atrophy and risk of acute adrenal insufficiency if treatment is abruptly withdrawn. This highlights the importance of careful monitoring, dose tapering, and prophylactic measures when prescribing long-term steroid therapy.

Integrating Physiology and Clinical Presentation

Cushing’s disease vividly illustrates the principle that “too much of a good thing can be harmful.” Cortisol is essential for survival during stress, enabling the body to mobilize energy substrates, maintain vascular tone, and restrain excessive inflammation. Yet, when these adaptive mechanisms are chronically activated, they become destructive. Muscle wasting, osteoporosis, insulin resistance, central obesity, immune suppression, and psychiatric symptoms all stem from the exaggerated expression of cortisol’s normal physiological effects. Similarly, the therapeutic benefits of glucocorticoids in suppressing inflammation are accompanied by the same liabilities when therapy is prolonged or unregulated. Thus, the clinical syndrome of Cushing’s is best understood as the pathological amplification of cortisol’s normal pharmacological profile.

Conclusion

Cushing’s disease and related forms of Cushing’s syndrome represent a classic endocrine disorder in which excess cortisol or glucocorticoid exposure produces a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. These include central obesity, muscle weakness, thin skin, striae, osteoporosis, diabetes, hypertension, immune suppression, mood disturbances, reproductive dysfunction, and more. Each symptom can be explained by the physiological and pharmacological effects of glucocorticoids on metabolism, connective tissue, bone, the immune system, cardiovascular regulation, and the brain. While glucocorticoids remain indispensable as medicines for controlling inflammation and autoimmunity, their long-term use must be carefully balanced against the risk of inducing iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome. Ultimately, the study of Cushing’s disease underscores the critical importance of hormonal balance, the interconnectedness of endocrine regulation, and the delicate trade-offs inherent in the use of powerful pharmacological agents.

Leave a Reply