Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are among the most abundant biological entities on Earth. Among these, the T4 bacteriophage (commonly referred to as the T4 virus) stands out as a well-researched model organism (Yap & Rossman, 2014). It infects Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria and has been extensively used in molecular biology and genetics. This article examines the structure, life cycle, and broader significance of the T4 virus, highlighting why it remains a key subject of study in virology and representative of viruses generally.

1. Historical Background

The discovery of bacteriophages dates back to the early 20th century, with researchers like Frederick Twort and Félix d’Hérelle noting their ability to destroy bacterial cultures. The T4 phage became a central research tool during the mid-20th century, particularly through the work of scientists like Max Delbrück, Salvador Luria, and Alfred Hershey. Their studies on T4 and related phages helped establish foundational principles in molecular genetics, such as the nature of genetic recombination and the central dogma of molecular biology.

2. Structure of the T4 Virus

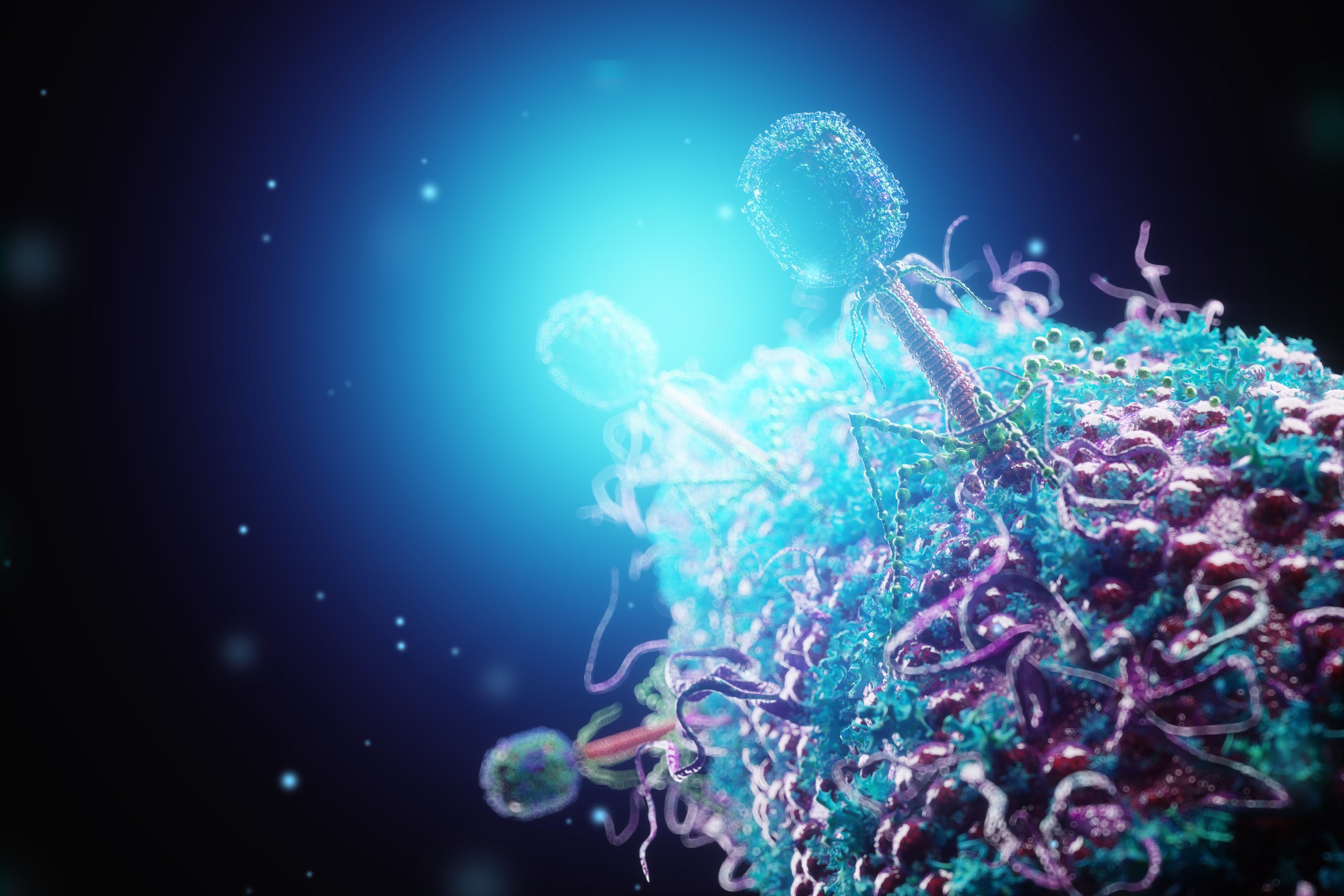

The T4 virus has a complex structure, typical of many tailed bacteriophages in the order Caudovirales, family Myoviridae. It has a head-tail morphology, specialized for infecting bacterial cells (Leiman et al., 2003).

-

Capsid (Head): The head is an icosahedral protein shell that encases the viral DNA. It measures about 90 nm in length and 75 nm in width. It contains approximately 170,000 base pairs of double-stranded DNA encoding nearly 300 genes.

-

Tail: The tail is a long, contractile tube surrounded by a sheath. At the base of the tail is a complex structure called the baseplate, which has tail fibers extending from it. These fibers are critical for recognizing and binding to specific receptors on the bacterial surface.

-

Tail Fibers: The six long tail fibers and six short tail spikes play a role in attachment and penetration of the host cell wall. These fibers identify and bind to specific molecules on the E. coli surface, ensuring host specificity.

3. Life Cycle of the T4 Virus

The T4 phage follows a lytic cycle, a process that results in the destruction of the host cell. The entire cycle is remarkably efficient and completes in about 25 minutes under optimal conditions.

Step 1: Attachment (Adsorption)

The T4 phage uses its tail fibers to recognize and attach to specific receptors on the surface of E. coli. These receptors are usually outer membrane proteins or lipopolysaccharides.

Step 2: Penetration

Once attached, the tail sheath contracts like a syringe, driving the tail tube through the bacterial envelope. The viral DNA is then injected into the host cytoplasm, leaving the empty capsid outside.

Step 3: Biosynthesis

Inside the host, the phage hijacks the bacterial machinery to transcribe and translate its genes. The T4 genome is highly ordered and is transcribed in three phases:

-

Early genes initiate takeover of the host and prepare for DNA replication.

-

Middle genes focus on DNA metabolism.

-

Late genes encode structural proteins for the assembly of new phage particles.

Importantly, the T4 virus encodes its own DNA polymerase and other replication enzymes, allowing efficient and accurate replication of its genome.

Step 4: Assembly (Maturation)

Phage components are assembled in a stepwise fashion:

-

The capsid is assembled and filled with DNA (Rao & Black, 2010).

-

The tail is built separately and then attached to the filled capsid.

-

Tail fibers and baseplates are added last to form mature virions.

Step 5: Lysis and Release

The T4 phage encodes lytic enzymes (like lysozyme) that degrade the bacterial cell wall, leading to osmotic rupture and release of progeny phages. A single E. coli cell can release over 100 new virions, each ready to infect new hosts.

4. Genetic and Molecular Biology Insights

The T4 phage has been pivotal in uncovering numerous molecular biology principles. Its relatively large genome and sophisticated replication strategy make it an excellent model system. Some key insights derived from T4 studies include:

-

DNA Replication: T4’s DNA replication system includes enzymes like helicase, primase, DNA polymerase, and ligase. Studies on these proteins contributed to our understanding of eukaryotic DNA replication as well.

-

Gene Regulation: The tightly controlled expression of early, middle, and late genes in T4 infection demonstrates a model of temporal gene regulation.

-

Recombination and Repair: T4 exhibits genetic recombination, providing early evidence for homologous recombination mechanisms. It also encodes repair enzymes that help maintain genetic fidelity during replication.

-

RNA Processing: Some T4 genes undergo mRNA processing and splicing, rare features in prokaryotic systems.

This bacteriophage T4 does not undergo lysogeny.

T4 is a strictly lytic phage, meaning it only follows the lytic cycle, which results in the infection, replication, and destruction (lysis) of the host Escherichia coli cell.

Why T4 Doesn’t Do Lysogeny:

-

Lysogeny is a process where a phage integrates its DNA into the host genome and remains dormant (as a prophage) without killing the host.

-

This is characteristic of temperate phages, like lambda (λ) phage.

-

T4, however, is a virulent phage—it does not integrate its genome into the host’s chromosome or enter a latent state.

-

Its infection always leads to active replication, assembly of new phage particles, and host cell lysis.

Summary:

| Feature | T4 Phage | Lambda Phage |

|---|---|---|

| Life Cycle | Lytic only | Lytic or Lysogenic |

| Integration into host DNA | No | Yes |

| Prophage formation | No | Yes |

| Temperate/Virulent | Virulent | Temperate |

If you’re comparing phages or studying phage therapy, this distinction is important—virulent phages like T4 are preferred for therapeutic uses because they reliably kill their bacterial hosts.

5. Evolutionary and Ecological Role

Bacteriophages like T4 play essential roles in bacterial population dynamics and genetic exchange in ecosystems. They act as natural predators of bacteria and help control microbial populations. Phages are also major drivers of horizontal gene transfer, contributing to bacterial evolution and diversity.

The arms race between phages and their bacterial hosts has led to the evolution of bacterial defense mechanisms, such as restriction-modification systems and the CRISPR-Cas system—both of which were initially discovered through phage research.

6. Applications in Biotechnology and Medicine

T4 phage research has also led to practical applications:

-

Phage Therapy: With rising antibiotic resistance, interest in using bacteriophages to treat bacterial infections has surged. T4-like phages are being explored as alternatives or complements to antibiotics.

-

Biotechnology Tools: T4 enzymes like DNA ligase and DNA polymerase have been adapted for use in molecular cloning and PCR.

-

Nanotechnology: The T4 phage’s structural proteins and DNA-packaging motors are being investigated for use in nanotechnology and targeted drug delivery systems.

-

Vaccine Platforms: Engineered T4 capsids have been tested as platforms for displaying antigens in vaccine development.

The T4 bacteriophage is a remarkable biological entity that has profoundly influenced our understanding of molecular biology, genetics, and virology. Its detailed structure, efficient lytic life cycle, and genetic complexity have made it a powerful model system. Beyond its scientific value, T4 continues to offer promising applications in biotechnology and medicine. As researchers continue to explore its capabilities and mechanisms, the T4 virus remains a cornerstone of molecular science and a testament to the power of viruses in shaping life.

References

Leiman, P. G., Kanamaru, S., Mesyanzhinov, V. V., Arisaka, F., & Rossmann, M. G. (2003). Structure and morphogenesis of bacteriophage T4. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences CMLS, 60(11), pp. 2356-2370

Rao, V. B., & Black, L. W. (2010). Structure and assembly of bacteriophage T4 head. Virology Journal, 7(1), 356

Yap, M. L., & Rossmann, M. G. (2014). Structure and function of bacteriophage T4. Future microbiology, 9(12), pp. 1319-1327. .

Leave a Reply