Introduction

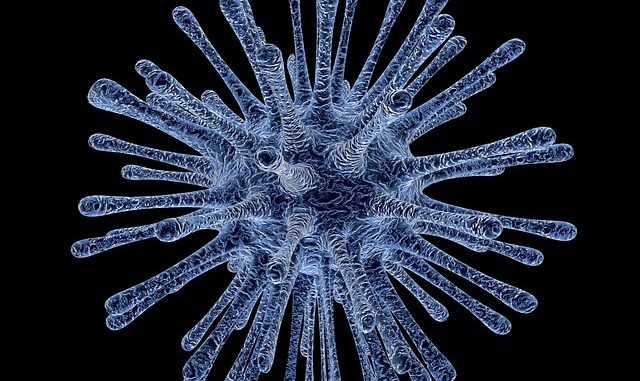

Lentiviruses are a genus of viruses within the family Retroviridae, characterized by their ability to integrate into the host genome and establish persistent infections. Named after the Latin word “lente” meaning “slow”, lentiviruses typically cause chronic diseases with long incubation periods. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the causative agent of AIDS, is the most well-known member of this group. In the past two decades, lentiviruses have become powerful tools in biotechnology and medicine, particularly through the development of lentiviral vectors—engineered versions of the virus used for gene delivery in research and therapy.

Gene therapy is currently their most powerful application. Why? Because they can efficiently infect both dividing and non-dividing cells by integrating their reverse-transcribed RNA genome in a host genome.

This article explores the biology of lentiviruses, the engineering of lentiviral vectors, and their broad applications, highlighting their strengths, limitations, and future prospects.

1. Biology of Lentiviruses

1.1 Structure and Genome

Lentiviruses are enveloped viruses containing a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome approximately 9.7 kb in length. The genome is encapsidated within a cone-shaped core made of the viral protein p24. Surrounding the core is the viral envelope, derived from the host cell membrane, embedded with viral glycoproteins such as gp120 and gp41 in the case of HIV.

The genome encodes for:

-

Structural proteins (gag, pol, env)

-

Regulatory proteins (tat, rev)

-

Accessory proteins (nef, vif, vpr, vpu)

The gag gene encodes core structural proteins, pol encodes enzymes (reverse transcriptase, integrase, and protease), and env encodes envelope glycoproteins.

1.2 Life Cycle

The lentiviral life cycle includes:

-

Entry: Viral envelope glycoproteins bind to receptors on the host cell membrane, followed by fusion and entry.

-

Reverse transcription: Viral RNA is reverse-transcribed into double-stranded DNA by reverse transcriptase.

-

Integration: The viral DNA is transported into the nucleus and integrated into the host genome by integrase. This allows infection of both dividing and non-dividing cells, a key feature distinguishing lentiviruses from other retroviruses.

-

Transcription and translation: The integrated provirus is transcribed by the host RNA polymerase II to produce viral RNAs and proteins.

-

Assembly and release: New viral particles are assembled at the plasma membrane and released by budding, acquiring their envelope in the process.

-

Maturation: Viral protease cleaves polyproteins into functional units, rendering the virus infectious.

1.3 Host Range

Natural lentiviruses infect a range of mammalian species, including primates (HIV, SIV), cats (FIV), horses (EIAV), and sheep (VISNA-Maedi virus). Through pseudotyping—modifying viral envelope proteins—lentiviruses can be engineered to infect a wide variety of cell types, including human cells, thereby broadening their applications.

2. Lentiviral Vectors

2.1 Development and Design

Lentiviral vectors are modified lentiviruses that have been rendered replication-incompetent for safety. The goal is to retain the efficient gene delivery machinery of the virus while eliminating pathogenicity.

Key design features:

-

Self-inactivating (SIN) vectors: A deletion in the U3 region of the 3’ LTR eliminates enhancer/promoter activity after integration, enhancing safety by reducing insertional mutagenesis.

-

Split packaging system: Vector components are divided across multiple plasmids (typically 3 or 4) to prevent the generation of replication-competent virus.

-

Transfer plasmid: Carries the gene of interest and necessary cis-acting elements (LTRs, Ψ packaging signal, RRE, etc.)

-

Packaging plasmid(s): Encode gag, pol, and sometimes rev.

-

Envelope plasmid: Encodes a heterologous envelope protein (commonly vesicular stomatitis virus G protein, VSV-G) to broaden tropism.

-

2.2 Transduction and Integration

Lentiviral vectors efficiently transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells, thanks to their ability to transport pre-integration complexes across the nuclear membrane. Once inside, they integrate into the host genome, enabling long-term expression of the transgene.

Transduction steps include:

-

Vector production in packaging cell lines (e.g., HEK293T)

-

Concentration and titration

-

Transduction of target cells, often enhanced by polybrene or spinoculation

-

Integration and stable gene expression

2.3 Advantages

-

Efficient integration into host genome

-

Stable, long-term expression of transgene

-

Transduction of non-dividing cells, including neurons and hematopoietic stem cells

-

Pseudotyping flexibility: Can be tailored to specific cell types or tissues

-

Relatively low immunogenicity compared to adenoviral vectors

2.4 Limitations and Risks

-

Insertional mutagenesis: Integration near oncogenes can lead to malignant transformation

-

Transgene silencing: Epigenetic modifications can shut down expression

-

Immunogenicity: While reduced, immune responses can still occur

-

Production complexity: Requires multiple plasmids and careful handling to prevent recombination

3. Applications of Lentiviral Vectors

3.1 Gene Therapy

Lentiviral vectors are used in clinical gene therapy to correct genetic defects by introducing functional genes. Key examples include:

a. Hematopoietic Disorders

-

β-thalassemia and sickle cell disease: Lentiviral vectors carrying modified β-globin genes have been used to restore hemoglobin function.

-

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD): Lentiviral gene therapy has shown success in correcting defective ABCD1 genes in hematopoietic stem cells.

b. Immunodeficiencies

-

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome (WAS) have been targeted with lentiviral vectors to restore immune function.

c. CAR-T Cell Therapy

Lentiviral vectors are commonly used to transduce T cells with chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) targeting cancers such as B-cell leukemias and lymphomas.

3.2 Neuroscience and CNS Disorders

Lentiviral vectors are used to deliver genes into neurons and glial cells for:

-

Parkinson’s disease: Delivery of enzymes like AADC or GDNF

-

ALS and Huntington’s disease: Silencing of mutant genes using shRNA or CRISPR systems

Their ability to transduce non-dividing neurons and provide sustained expression is crucial for these applications.

3.3 Basic Research

Lentiviral vectors are invaluable in molecular biology for:

-

Stable gene overexpression

-

RNA interference (RNAi) via shRNA

-

CRISPR-Cas9 delivery for genome editing

-

Reporter gene expression (e.g., GFP, luciferase)

They are commonly used to create stable cell lines, perform loss-of-function screens, and study gene function.

3.4 Vaccination

Lentiviral vectors are being explored as vaccine platforms, especially for HIV, malaria, and cancer immunotherapy. Their ability to induce both humoral and cellular immune responses makes them promising candidates.

4. Recent Innovations and Future Directions

4.1 Safer Vector Designs

-

Integration-deficient lentiviral vectors (IDLVs): Mutated integrase prevents integration, enabling transient expression—useful for vaccine applications and gene editing.

-

Targeted integration: Using integrases fused to DNA-binding domains (like zinc fingers or CRISPR-guided systems) to direct insertion into “safe harbor” loci such as AAVS1.

4.2 Combinatorial Technologies

-

CRISPR-Cas9 + lentiviral vectors: For genome-wide screens or precise editing.

-

Synthetic biology: Creating logic-gated vectors or inducible systems.

4.3 Clinical Expansion

Lentiviral-based therapies are being approved for broader indications:

-

Zynteglo (Bluebird Bio) for β-thalassemia is one of the first FDA-approved lentiviral gene therapies.

-

Trials are expanding for diseases like sickle cell anemia, multiple sclerosis, and inherited blindness.

4.4 Biomanufacturing Advances

Efforts are underway to improve large-scale production, purification, and regulatory compliance, including serum-free media, suspension cultures, and automated bioreactors.

Conclusion

Lentiviruses have evolved from notorious pathogens into powerful biotechnological tools. Their unique biology—particularly their ability to integrate into the genome of non-dividing cells—has made them indispensable in gene therapy, neuroscience, cancer immunotherapy, and basic research.

Lentiviral vectors offer stable gene expression, broad tropism, and versatility in design, yet safety concerns such as insertional mutagenesis remain important. With advances in genome editing, synthetic biology, and targeted integration strategies, the next generation of lentiviral vectors will likely be safer, more precise, and more effective.

As research continues and more therapies gain approval, lentiviral vectors are poised to play a central role in the future of personalized medicine and gene-based therapeutics.

![DNA. Nucleic acid purification. Okazaki fragments. PCR (digital PCR [dPCR], multiplex digital PCR, qPCR), DNA Repair, DNA Replication in Eukaryotes, DNA replication in prokaryotes, DNA barcoding](https://foodwrite.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/dna-geralt-pixaby-03539309_640-150x150.jpg)

Leave a Reply