1. Introduction

DNA methylation is a chemical modification of DNA where a methyl group (–CH₃) is added to specific nucleotides, most commonly cytosine bases in CpG dinucleotides (a cytosine followed by a guanine in the DNA sequence).

It’s an epigenetic modification — meaning it changes gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself. Think of it as “molecular punctuation” in your genome: it doesn’t rewrite the letters, but it affects how the sentence is read.

2. The Chemical Basis – The Mechanism of Methylation

-

Methyl group donor: S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) — provides the methyl group.

-

Target base: Most often cytosine at the 5′ position of the pyrimidine ring → 5-methylcytosine (5mC).

-

Catalyzing enzymes: DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) or methylases:

-

DNMT1 — maintenance methylation during DNA replication.

-

DNMT3A and DNMT3B — de novo methylation (establishing new methylation patterns).

-

DNMT3L — regulatory role, not catalytic.

-

SAM is then converted to S-adenosyl homocysteine (SAH).

DNMT1

- maintain the pattern of DNA methylation after DNA replication.

- requires a hemi-methylated DNA substrate and will faithfully reproduce the pattern of methylation on the newly synthesized strand.

- This enzyme ensure DNA methylation is ‘an automatic semi-conservative mechanism’.

DNMT3a & DNMT3b

- These methylases add methyl groups to CG dinucleotides that were previously unmethylated on both the strands.

- These enzymes reestablish the methylation pattern.

3. Where it happens

DNA methylation occurs in cells of fungi, non-vertebrates, vertebrates and plants but NOT insects and single-celled eukaryotes.

The addition of the methyl group is at the C-5 position of a cytosine.

In vertebrates:

-

Occurs mainly at CpG sites. The sequence context is 5’CG3′. The presence of guanine as the next nucleotide means methylation is virtually exclusive there.

-

Between 3 and 6% of DNA cytosine is methylated.

-

CpG sites are unevenly distributed — many are clustered in CpG islands (often near gene promoters).

-

Promoter CpG methylation is often associated with gene silencing.

In plants and some invertebrates:

-

Methylation can also occur at CpHpG and CpHpH (H = A, T, or C) sites.

-

In plants, 30% of DNA cytosine is methylated.

Mammalian Genomes

The human genome is not methylated uniformly and contains regions of unmethylated segments interspersed by methylated regions.

In contrast to the rest of the genome, smaller regions of DNA which are called CpG islands, range from 0.5 to 5 kb. These occur on average every 100 kb and have distinctive properties. Such regions are not normally unmethylated. Approximately half of all the genes in humans have CpG islands. These islands are present on both housekeeping genes and genes with tissue-specific patterns of expression.

4. Biological Functions

A. Gene expression regulation

-

Methylated promoters → generally repressed transcription.

-

Unmethylated promoters → generally active transcription.

-

Mechanisms:

-

Directly blocks transcription factor binding.

-

Recruits methyl-binding proteins (e.g., MeCP2) → recruit histone deacetylases → chromatin compaction.

-

B. Development

-

Patterns of methylation are set during embryogenesis and cell differentiation. Methylation itself is essential for embryonic development. Mice that lack maintenance DNA methyltransferase are retarded in their development and often die mid-gestation.

-

Tissue-specific methylation patterns define cell identity.

C. X-chromosome inactivation

-

One X chromosome in female mammals is inactivated by methylation.

D. Genomic imprinting

-

Certain genes are expressed from only one parental allele due to methylation.

E. Transposon silencing

-

Methylation suppresses repetitive DNA elements to maintain genome stability.

5. Dynamic Nature and Demethylation

Active demethylation

-

Carried out by TET enzymes (Ten-eleven translocation proteins), which oxidize 5mC → 5hmC → 5fC → 5caC, followed by base excision repair.

Passive demethylation

-

Loss of methylation during replication if DNMT1 fails to methylate the new strand.

6. DNA Methylation and Disease

-

Cancer: Tumors often show global hypomethylation (genomic instability) and hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters.

Global hypomethylation is observed in neoplastic cells which may induce neoplastic transformation. This neoplastic transformation produces genomic instability, abnormal chromosomal structures and in activating oncogenes.

DNA hypermethylation produces the inactivation of tumour-suppressor genes: p16 and BRCA1 It also inactivates DNA repair genes such as MLH1 and MGMT.

-

Neurological disorders: Rett syndrome (MeCP2 mutation), Fragile X syndrome (CGG expansion hypermethylation of FMR1).

-

Aging: Methylation patterns change predictably with age — basis of “epigenetic clocks.”

-

Metabolic and autoimmune diseases: Aberrant methylation patterns found in diabetes, lupus, etc.

7. Laboratory Analysis of DNA Methylation

Studying DNA methylation in the lab requires converting or detecting the chemical modification at specific sites or genome-wide. There are excellent reviews on the subject which cover bother general and then more specific areas (Shen & Waterland, 2007; Kurdyukov & Bullock, 2016).

We’ll cover the main techniques in four categories:

A. Bisulfite Conversion-Based Methods (Clark et al., 2006; Patterson et al., 2011)

Principle:

-

Sodium bisulfite treatment converts unmethylated cytosines → uracil (read as thymine after PCR), but methylated cytosines remain as cytosine.

-

This creates a methylation-dependent sequence difference detectable by PCR or sequencing.

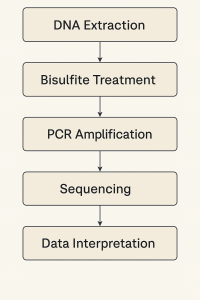

Key steps:

-

DNA extraction — high-quality genomic DNA.

-

Bisulfite treatment — DNA is denatured and treated with sodium bisulfite under acidic conditions.

-

PCR amplification — uracil-containing DNA is amplified (uracil read as thymine).

-

Analysis — sequencing or specific methylation-sensitive assays.

Applications:

-

Bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) — gold standard; can be:

-

Sanger sequencing for small regions.

-

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) for genome-wide mapping.

-

-

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) — uses primers specific to methylated or unmethylated sequences after conversion.

-

Pyrosequencing — quantitative methylation at specific CpG sites.

Advantages:

-

Single-base resolution.

-

Well-established.

Limitations:

-

DNA degradation during treatment.

-

Cannot distinguish 5mC from 5hmC without additional steps.

B. Restriction Enzyme-Based Methods

Principle:

-

Some restriction enzymes are sensitive to methylation (e.g., HpaII cuts CCGG only if unmethylated; MspI cuts regardless of methylation).

-

Comparing digested vs. undigested patterns reveals methylation status.

Examples:

-

COBRA (Combined Bisulfite Restriction Analysis) — combines bisulfite conversion with restriction digestion.

-

MRE-seq — methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme sequencing.

Advantages:

-

Simple, inexpensive.

Limitations:

-

Low resolution (depends on enzyme recognition sites).

-

Cannot survey all CpGs.

C. Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP)

Principle:

-

Uses antibodies specific for 5-methylcytosine to pull down methylated DNA fragments.

-

DNA is then analyzed by qPCR, microarrays (MeDIP-chip), or sequencing (MeDIP-seq).

Steps:

-

Fragment genomic DNA (sonication).

-

Incubate with anti-5mC antibody.

-

Immunoprecipitate methylated fragments.

-

Analyze enriched DNA.

Advantages:

-

Works genome-wide.

-

No harsh chemical treatment.

Limitations:

-

Resolution depends on fragment size (~150–300 bp).

-

Cannot distinguish 5mC from 5hmC (unless using specific antibodies).

D. Emerging Single-Molecule and Long-Read Methods

-

Nanopore sequencing

-

Detects methylation directly from changes in ionic current as DNA passes through a nanopore.

-

No chemical conversion required.

-

Works for 5mC and 5hmC.

-

-

PacBio SMRT sequencing

-

Detects DNA modifications from polymerase kinetics during sequencing.

-

Advantages:

-

Direct detection, no bisulfite.

-

Long reads capture methylation in context.

Limitations:

-

Higher error rates (improving with technology).

-

Expensive.

8. How DNA Methylation is Done in the Laboratory (Experimental Workflow)

Let’s walk through a standard methylation analysis from sample to results.

Step 1: Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

-

Sources: blood, tissue biopsy, cell cultures.

-

DNA extraction kits or phenol–chloroform extraction.

-

Quality check: absorbance ratios (A260/A280), gel electrophoresis.

Step 2: Bisulfite Conversion (most common starting point)

-

Denature DNA (heat, alkaline treatment).

-

Treat with sodium bisulfite → cytosine deamination.

-

Purify converted DNA (removes bisulfite and byproducts).

-

Quality control: check DNA recovery.

Step 3: Target Amplification

-

PCR with primers designed for bisulfite-converted DNA.

-

For MSP: design two sets of primers — one for methylated, one for unmethylated sequence.

Step 4: Analysis

Option A: Sequencing

-

Sanger sequencing for targeted regions.

-

WGBS for genome-wide maps.

Option B: Quantitative assays

-

Pyrosequencing for % methylation at each CpG.

-

High-resolution melting analysis for relative methylation.

Step 5: Data Interpretation

-

Compare methylation profiles between samples (e.g., cancer vs. normal tissue).

-

Correlate methylation with gene expression (via RNA-seq or qPCR).

9. Controls and Quality Assurance

-

Include fully methylated DNA (positive control).

-

Include fully unmethylated DNA (negative control).

-

Monitor conversion efficiency (non-CpG cytosines should be fully converted in bisulfite assays).

10. Applications of DNA Methylation Analysis

-

Cancer diagnostics — detecting methylation of tumor suppressor genes in blood (liquid biopsy) (Jeddi et al., 2024).

-

Forensics — tissue type prediction from methylation patterns.

-

Aging research — epigenetic clocks.

-

Developmental biology — tracking cell fate decisions.

-

Environmental epigenetics — impact of diet, toxins, stress on methylation.

-

Neurobiology — linking methylation changes to learning, memory, psychiatric conditions.

11. Challenges and Limitations

-

Distinguishing 5mC from 5hmC — standard bisulfite cannot do this; oxidative bisulfite sequencing or TET-assisted bisulfite sequencing is needed.

-

Heterogeneity — bulk tissue samples may contain mixed cell types with different methylation.

-

DNA damage — bisulfite treatment is harsh and can degrade DNA.

-

Interpretation — methylation is context-dependent; not all methylation changes alter gene expression.

12. Future Directions

-

Single-cell methylation sequencing — maps methylation at cellular resolution.

-

Direct detection with nanopore/PacBio — avoiding chemical conversion.

-

Integration with other epigenetic marks — understanding the interplay with histone modifications and chromatin structure.

-

Epigenome editing — targeted methylation/demethylation using CRISPR–DNMT or CRISPR–TET fusions to study functional consequences.

13. Summary Table of Key Methods

| Method | Principle | Resolution | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite sequencing | C→T conversion unless methylated | Single base | Gold standard | DNA degradation |

| MSP | Bisulfite + PCR with methylation-specific primers | CpG-specific | Fast, cheap | Yes/no only |

| Pyrosequencing | Sequencing-by-synthesis post-bisulfite | CpG-specific, quantitative | High accuracy | Limited read length |

| MeDIP-seq | Antibody enrichment | ~150–300 bp | Genome-wide | No base resolution |

| Nanopore | Direct detection | Single base | No conversion | High error rate |

| Restriction enzyme | Methylation-sensitive digestion | Enzyme sites | Simple | Limited coverage |

14. Key Takeaways

-

DNA methylation = adding a methyl group to cytosine (mainly at CpG sites).

-

Essential for development, gene regulation, genome stability.

-

Aberrant methylation = hallmark of many diseases.

-

Laboratory analysis uses bisulfite conversion, restriction enzymes, antibody-based methods, or direct sequencing.

-

Technology is moving toward single-molecule, real-time, and single-cell methylation mapping.

References

Clark, S. J., Statham, A., Stirzaker, C., Molloy, P. L., & Frommer, M. (2006). DNA methylation: bisulphite modification and analysis. Nature Protocols, 1(5), pp. 2353-2364.

Jeddi, F., Faghfuri, E., Mehranfar, S., & Soozangar, N. (2024). The common bisulfite-conversion-based techniques to analyze DNA methylation in human cancers. Cancer Cell International, 24(1), 240.

Kurdyukov, S., & Bullock, M. (2016). DNA methylation analysis: choosing the right method. Biology, 5(1), 3 (Article).

Patterson, K., Molloy, L., Qu, W., & Clark, S. (2011). DNA methylation: bisulphite modification and analysis. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE, (56), 3170.

Shen, L., & Waterland, R. A. (2007). Methods of DNA methylation analysis. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 10(5), pp. 576-581 (Article).

![DNA. Nucleic acid purification. Okazaki fragments. PCR (digital PCR [dPCR], multiplex digital PCR, qPCR), DNA Repair, DNA Replication in Eukaryotes, DNA replication in prokaryotes, DNA barcoding](https://foodwrite.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/dna-geralt-pixaby-03539309_640-150x150.jpg)

Leave a Reply